#36 Industrialisation: the USA and Germany

During the 19th century, the world’s most powerful nations industrialised. Industrialisation was a historically unique process. Industrialisation involved the creation of ‘infrastructure’, communication through roads, railways, and canals; the building of massive factories, producing a huge volume of goods, and most of society living close together in urban housing side by side. None of this had ever occurred before in all the world’s history. Britain was out in front in the 19th century as she led the way with industrialisation, however, the USA caught up, and Germany too by the end of the century from a slow start. All three societies came to Industrialisation through their unique histories, so there were many differences. This blog illustrates two of these differences between the USA and Germany.

Industrialisation and capitalism had specific new characteristics which would overwhelm all societies that strove to catch up to avoid being conquered and colonised. All involved

Implementing a new centralised financial system we now call banking and finance

The development of new sciences and technology,

The adoption of a new system of government largely devoid of ancient Kings or Queens

The exploitation of labour either as slaves, indentured labour or cheap domestic labourers. It was this aspect of the new systems that caused upheaval and struggle on a gigantic scale.

The USA

The USA began to grow rapidly during the early years of the 19th century. The fact that the continent of North America was not finally conquered, and that large parts of the economy were still dominated by chattel slaves and large plantations, should not blinker us. The American invasion and destruction of the indigenous people’s economy prepared the way for full-scale industrialisation. There were no ancient Popes or Emperors to inhibit the rapid growth of private property and ownership of land. The preconditions for full-scale capitalism, at least along the East Coast and around the Great Lakes, were already in place by 1815.

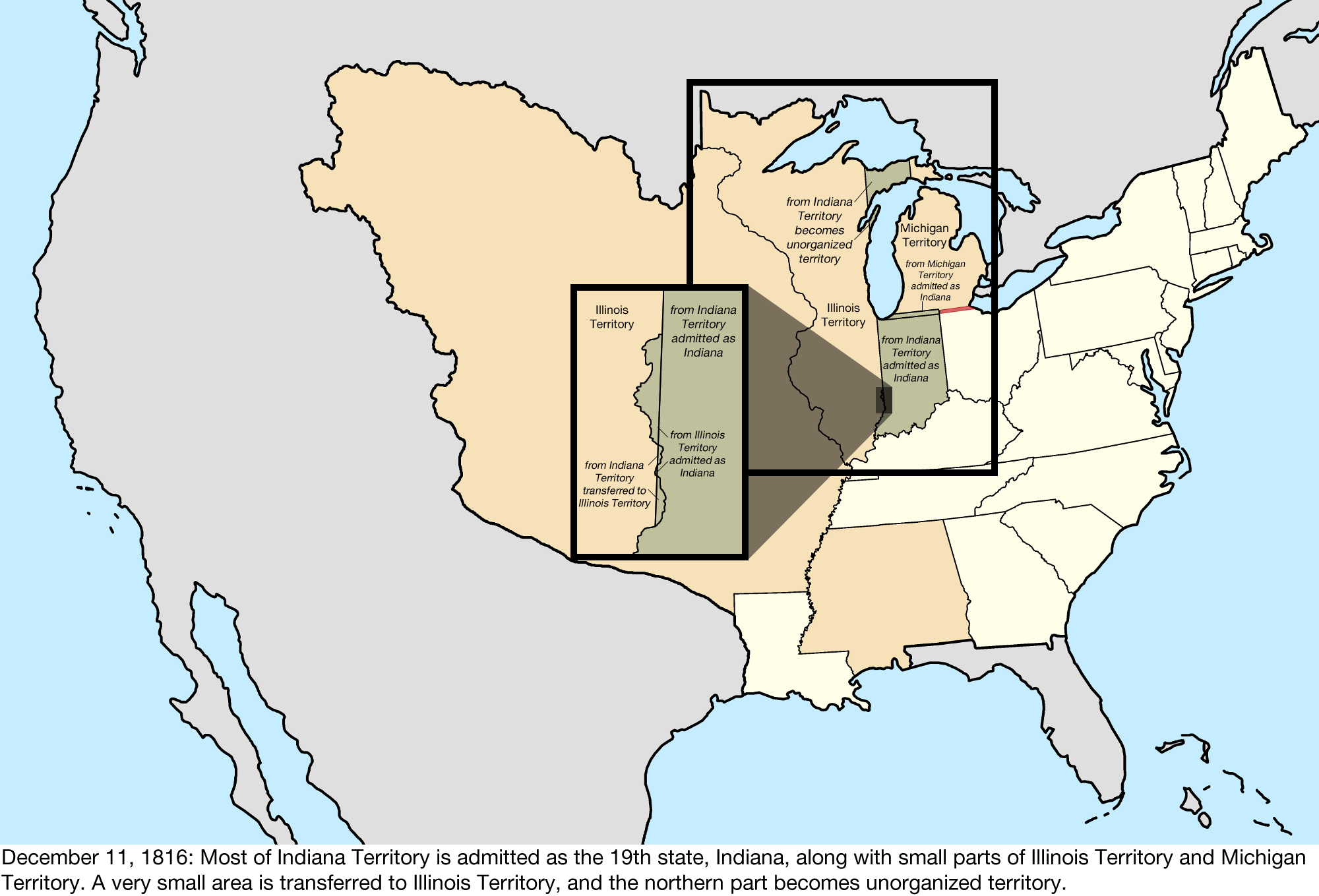

Map of the USA, December 11th, 1816. By Golbez, CC BY-SA 4.0. Retrieved from Wikipedia.

Map of the USA, September 29, 1813. By Golbez, CC BY-SA 4.0. Retrieved from Wikipedia.

During the course of the century, both the people and the US military pressed westwards, slowly defeating the horse-riding militarised indigenous peoples who resisted. Once the repeater rifle came into general use the last resistance of the indigenous American peoples was finally ended. The effort to create a United States, to destroy its indigenous civilisation, took most of the century. The Civil War and the wars against the indigenous peoples focused much political attention. Above all else, land was abundant. All else favoured purely capitalist development. And once the southern states were liberated from slavery, an entrepreneurial economy was free to develop.

The USA had several advantages over any other rival in the 19th century, including the states to their south, Brazil, Chile and the Argentine. The first advantage has already been mentioned: there was no ancient regime to overthrow, no social and religious baggage to remove. The sheer size of the American continent was an inhibition, but equally an advantage once integrated by the railway. The USA, like Brazil or the Argentine, had a huge internal market to satisfy, with raw materials on its doorstep: iron ore, copper, lead, zinc, nickel, aluminium, oil and - if not available within the USA or one of the other South American nations - available within the whole American continent.

So why did the USA industrialise, but others to their south did not? Why did the southern economies remain mainly agricultural? This question seems not to have been asked in the literature. Governments of countries such as Brazil and Argentina had been taken over by their settlers, as did the USA if only 50 or so years later. One possible explanation is that the leading cadres in the USA came from Protestant stock, while all southern American states had been settled by Spanish or Portuguese Catholics. Catholicism was the ideological addition to the 'ancien regime', which remained when the governments had been overthrown. However, the dominance of Roman Catholic traditions cannot be a sufficient explanation on its own, but it is perhaps moving in the right direction.

The USA was the first single continent to industrialise, and from early on it illustrated the many advantages of size.

From the early 1830 and 40s, railway expansion opened up the vast American economy. Britain and their merchant banks were the sources of much of the early capital invested in rail infrastructure, including the early iron rails. Rapidly, American capital, entrepreneurship and management came to the fore. The railroad became the nation’s first big business enterprise. Andrew Carnegie became the leading businessman in the steel industry. The sheer scale of the industry provided an opportunity to supply all the ingredients needed to build railways. By the 1860s, half of all iron was US-made, and by the 1880s, 75% of the steel was too.

Miles of railroads built per year:

| Year | Miles of Railroad Built |

|---|---|

| 1830 | 40 |

| 1840 | 401 |

| 1850 | 1261 |

| 1860 | 1500 |

| 1870 | 5658 |

| 1880 | 5006 |

| 1900 | 4894 |

From 1900, the number of miles declined annually, down to 400 miles a year in the 1920s.

Source: C Freeman, The Third Kondratieff Wave, The Age of Steel Electrification and Imperialism, Chapter 6.

Alongside the railroads came the telegraph, coal, iron, and steel industries. There was a crucial nexus between the growth of the railroads and the forward surge in the American economy. Equally important in the USA was the growth of canals, lakes, and water transport. The steamships came into their own here. All of this made a domestic agriculture market possible to feed people in the growing towns and cities. Alongside the regularity and volume of transport came the factory system throughout the USA. The railway network provided the infrastructure for the wave of structural change which began the American industrialising process.

W. W. Rostow in the 1960s wrote a book entitled The Stages of Economic Growth and for a time it became compulsory reading for students in development studies. Rostow took his analysis from US experience in the 19th century and used the phrase 'take-off', which refers to the coming together of the steel industries and engineering which led to regular ongoing growth.

Good quality steel led a hundred diverse industries from bridges, cranes, large buildings, machines, hand and power tools, turbines, and pylons, to ammunition, artillery, tanks, and many more new industries. Steel was the background to the killing fields of the first global war in 1914.

US entrepreneurs copied British innovations before beginning to develop their own, as happens in all newly industrialising processes. A smart innovator had managed to copy the new inventions of cotton manufacture from Britain in the 1820s; the future was written. The industrialising North and slave-owning South along with the East Coast of the USA became dependent on each other. The British inventions of the spinning jenny in the 1820s and the industrialisation of cotton manufacturing rapidly spread across the Atlantic at the beginning of the 19th century. American large-scale urban growth began on the backs of cotton, railways, and slavery. By the end of the 19th century, the USA’s Gross Domestic Product was greater than Germany or Britain. By 1900 the increase in wealth in the USA was ahead of any nation in Europe.

The Americans had only just begun to step onto the world stage by 1900. Admittedly, the Monroe Doctrine of 1823 was hostile to European colonialism in the southern continent, largely focused on Spain and Portugal. American ships were aggressively pursuing colonial policies in the 1850s as Commander Perry threatened Japan. The North Americans did not begin to colonise as part of their foreign policy until late in the 19th century when they invaded the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico in 1898 and took the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua from the Spanish between 1912 and 1914.

But there is plenty of evidence that some Americans in positions of power were thinking carefully about world power around the end of the nineteenth century. Though it would take another 50 years for the USA to assert their global dominance after 1945. We know some of the main thrusts of American thinking from the work of John Nicholas Spykman. “Americas Strategy in World Politics: The United States and the Balance of Power”. This was first published in 1942 and examined the world in detail and the role of the USA.

American naval generals were examining British thinking about the command of the seas and why this was so important. The Monroe Doctrine had deterred the Europeans from developing their colonisation in the south. By the end of the century, France, Germany, and Britain had all challenged the USA over naval dominance in the West Indies. Britain had been deterred in the south by their exposed position in Canada.

The Americans set about removing British domination of the Caribbean. The Americans wished to control the building of a canal from the Caribbean to the Pacific and did not want British interference. At the end of the century, when all these issues came to a head, the British were grossly overstretched around the world. In southern Africa, the British were occupied by the Jamison Raid, the Kruger Telegram, and the Boer War, just when there was a dispute with Venezuela and the Fashod disputes over control of the upper Nile in 1898. In China, they were dealing with the Boxer Rebellion 1899-1902. They had strained relations with Russia. In such circumstances, British power in the Caribbean gave way to American pressure.

The German and British naval programmes kept clear of the Americas and concentrated their forces on the North Sea and around Europe. The USA was just beginning to flex their imperial muscles by 1914.

Map of the USA, January 1st 1909. By Golbez, CC BY-SA 4.0. Retrieved from Wikipedia.

Germany

At the beginning of the 19th century, Germany was a motley collection of around 300 mini feudal states, each a part of the Holy Roman Empire and the overarching Hapsburg Emperor, each with a monarch and army. 70 years later, this collection of German-speaking statelets had coalesced into a mighty nation ready to challenge Britain for world leadership. The story of how this change occurred is yet one more example of the transformations occurring across the world leading to capitalist industrialisations.

The French Revolution and subsequent invasions by Napoleon blew the old political structures apart. Prussia was the largest mini-state, which had already become Protestant. During this period, lands changed hands and Napoleon created a Confederation of the Rhine (as it turned out this would be the first stage of German unification) which he allied to France. This forced the Hapsburgs to give up the title of the Holy Roman Empire and exposed the German peoples to ideas of the revolution. New rights and freedoms of the press and religion were granted. It was a period of intense intellectual turmoil for all the mini-states.

Prussia was not part of the confederation but had been defeated by Napoleons forces in 1806 at the battles of Jena and Auerstedt. As a response, Prussia instituted sweeping reforms; they created a national guard, compulsory military service, and a trained officer corps. Serfdom was abolished and the land was opened to all. By 1813, Prussia was ready to fight again, and in alliance with Austria and Russia defeated Napoleon’s forces at the battle of Leipzig.

At the Congress of Vienna in 1814/15, there were only forty-odd German statelets remaining and these were able to keep their territories gained during the Napoleonic era. Prussia also gained new territory at the congress; she took parts of Swedish Pomerania and the kingdom of Saxony. The Confederation of German States also remained, this time including Prussia (the second stage of unification). The purpose was a common defence and the promotion of trade. German nationalism for the first time appeared and much of feudal order had been swept away.

The German Confederation in 1815. By TRAJAN 117, CC BY-SA 3.0. Retrieved from Wikipedia.

It wasn't going to be so easy. The two most powerful central European states - Prussia and Austria - feared the new liberal ideas and wished to return to the pre-Napoleonic era. Guilds, artisans, and nobles feared the loss of privilege and power and, as expected, they resisted change. The years between 1815 and 1871 were politically turbulent. Freedoms granted in some states were rescinded, but then returned. In 1830 a new revolution in France ruined many of the reforms of the previous decade.

At the same time over this half-century, as all these political changes were occurring, the industrial process was felt throughout Western Europe. The economies were deregulated, guilds and nobles lost their ancient privileges, land became a commodity to be bought and sold. Small-scale home-based industries fell away as factory urban growth hit the towns. Mechanisation and political change were happening simultaneously across much of Western Europe. With these changes, a new middle and educated class was growing, alongside changes in agriculture, and with a healthier population.

The third stage of German Unification was the German Customs Union of 1834, the Zollverein. The Zollverein standardised currencies, taxes and customs paid at borders. Only Austria was left out. This allowed each German state to invest in roads and canals and start building railways. As a direct consequence, towns, industries, and a new working class grew, alongside emigration to the USA.

Then in 1848, Europe was swept by a new revolution. The ideas from the Americans and French Revolution came together, along with bad harvests. The revolution began in Sicily and rapidly spread to France and the German collection of states. The new urban middle and working classes joined in. Freedoms and new constitutions and parliaments were granted. For the first time, a German National Assembly discussed a national German parliament in Frankfurt. Again, the revolutions came to nothing as sufficient military force was used to suppress the uprising and return to the status quo. By 1851, all the changes made in 1848 had been annulled.

At this stage in the 19th century, German capitalist development was far behind Britain’s. In 1841 Freidrich List wrote his National System of Political Economy; he had severe doubts that Germany could ever succeed in catching up with Britain, so great were the differences in technology, productivity, skills, and exports. Then, in Rostow terms, Germany ‘took off’. By 1913, Germany was competing against Britain on equal terms. Only the USA was well ahead in productivity. Germany had developed its banks consciously to create industrial companies: perhaps the key difference.

Map of the German Empire within Europe, circa 1914. By Maix, CC BY-SA 3.0, retrieved from Wikipedia.

Recommended Reading

American 19th century economic history:

On USA 19th century Industrial History:

C Freeman, The Third Kondratieff Wave, The Age of Steel Electrification and Imperialism, University Press Scholarship Online, November 2003.

A.D.Chandler, The Railways: the nation’s first big business, Harcourt Brace 1965;

Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism, Harvard University Press 1990.

R. Fogel, Railroads and American Economic Growth, 1964.

J.A. Schumpeter, The Theory of Economic Development, Harvard University Press 1934; Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical and statistics Analysis of the Capitalist Process, McGraw Hill 1939.

Stephen Yafa, Cotton: the Biography of a Revolutionary, Faber Penguin 2005.

On USA early Foreign Policy:

Nicolas John Spykman, American Strategy in World Politics: The United States and the Balance of Power, Transaction Publishers 2007.

Copyright Notice. This blog is published under the Creative Commons licence. If anyone wishes to use any of the writing for scholarly or educational purposes they may do so as long as they correctly attribute the author and the blog. If anyone wishes to use the material for commercial purpose of any kind, permission must be granted from the author.

Before 1815, there had been no global world power. Today in the 21st century we have become used to living with a single dominant power. We are so used to this fact that no one questions it. It is possible that ancient China might have decided to become such a power; she had the technical shipbuilding knowledge, but she showed no interest. A world power needed a superior military force, a vibrant economy to support its military might, a navy able to travel across the world, and some purpose that encompassed the world.