#11 Understanding Colonialism: Competitive Colonialism & Defending Colonies

From 1500 to 1945, the major European colonising nations, France, Holland Spain, Portugal, and Britain saw each other as enemies. They fought each other both internally within Europe and externally across the world. This blog examines European antagonism across the world… The world of competitive colonialism.

This blog looks back over the long period when the peoples of the continent were at war with each other over religion and territory. It was taken for granted over the 450 years of colonial invasions that taking other people’s land was the ‘common sense’ of overseas policy. It was equally taken for granted that other colonising European nations were enemies.

Over 450 years from 1500 to 1945, the major European powers competed with one another over colonies. There were no established global rules until the 20th century. One of the purposes of the monopoly companies was to take colonies from other European powers, it is in this sense that European colonisation was a competitive process. The religious wars and conflicts between states within Europe were replicated across the globe. The Spanish and Portuguese were first off the block in the 15th century, invading and colonising the Americas. Within a hundred years, roughly from 1492 right through to 1945, the major powers of Europe - which included the Spanish, Portuguese, British, Russian, French, and Dutch - were all competing for colonial territory. Germany Japan, Italy and Belgium joined the fray in the second half of the 19th century.

These nations fought each other both in Europe and abroad: first in the Americas in the 17th century, and later in Africa or Asia in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. By the end of the 19th century, the new industrialising nations, (Germany Japan, Italy and Belgium) had joined the fight. The unwritten assumption was that a nation would ‘join the game', which meant defending the boundaries of 'your' colony against other belligerent colonising powers, and – importantly - invading and taking new territory.

Russia is an interesting case in our understanding of competitive colonialism. Other than the USA, the Russian Empire was the only land-based empire. The Russian state retained a king or queen and feudal court, basically unaltered throughout this period, and can usefully be understood as an ancient empire. Because her expansion was primarily eastwards across Siberia and the vast territory towards China, she was little troubled by other European marauding states. Russian expansion was left undisturbed by other Europeans looking for territory, except in Crimea and where the British feared she might invade the Ottoman empire in the North East territories where they feared she might invade Afghanistan and then India. The three 19th century wars; in Crimea (1953 - 1956) and Afghanistan (1839 – 1842 and 1878 - 1880) stopped Russian expansion towards Constantinople and India, as the British desired. But that still left a huge area of central Asia for Russian settlement and colonisation, without fear from any other colonising states.

From the beginning of the nineteenth century, international diplomacy became a major industry of government. European governments made short-term agreements with each other, but no country at this time had the resources to become globally dominant, as later seen in the 20th century. Though Britain did become relatively dominant during most of the 19th century when sterling was accepted as the major trading currency. Diplomacy there played a key role with the aim to avoid competitive colonialism.

Throughout the 19th century Britain was the worlds most powerful State. At Britain’s centre, the City of London, was considered the major global financial centre. Britain had technically developed her navy, so she could police sea lanes. She colonised an array of islands in the Mediterranean and the Pacific, where she set up naval facilities. These global elements of power allowed her to play a dominant diplomatic role. But no European power played the role on the world stage that the United States has done since 1945. No European power had the military resources to dominate on a global level, although Britain did her level best to have the worlds overwhelming fire and naval power.

Competitive colonialism was the order of the day, and diplomacy mitigated the sharp edge of national greed. Two examples illustrate this nicely. First, even though Britain bragged to her people about her dominance on the world stage, her civil service knew full well that she was a small if wealthy nation: too small and weak to wield her military power around the world. To make up what she lacked in guns and muscles, she used the military forces of her colonies. India became the ideal colony to achieve this goal.

Before she was colonised, India’s five hundred or so centralised kingdoms all had their military forces. As these kingdoms were conquered by the forces of the British East India Company, the kingdoms’ military forces were removed from the control of the local Kings and used for purposes designated by the East India Company.

Readers of my earlier blog on Monopoly companies may remember how I described ships that were sent out across the world as virtually pirate vessels armed to fight against both indigenous peoples as well as other European states wishing to take the land. Colonisation before the 2nd half of the 19th century was primarily undertaken on behalf of their State in Europe. The monopoly trading companies were profit making entities which acted as if they were the state which had created the monopoly. In the case of India, the British East India company was the colonising invader. Only later after the Indian rising against the British East India company in 1857 did the British state take over.

When the navy of the British state invaded China in the 1840s, they used the British East India Company’s Indian military forces led by British commanders. India provided Britain with an army comprising of a huge number of soldiers, paid for out of Indian taxes.

The second example where the need to defend colonial colonies illustrates Britain’s global imperial vulnerability. The Suez Canal was built in the middle of the 19th century, paid for out of loans to the then Egyptian state from London and Paris, and repaid from Egyptian taxes. The canal brought huge benefit to British and French traders, reducing the time of transport between the east and west by many weeks. England wished to control the canal; but when the loans were not repaid, the serious possibility arose that France would invade and colonise Egypt, which was clearly against English interests. Britain took over the canal, in part to stop the French from invading and in part to ensure that the loans were repaid. The Egyptian peasants had to pay higher and higher taxes for this purpose.

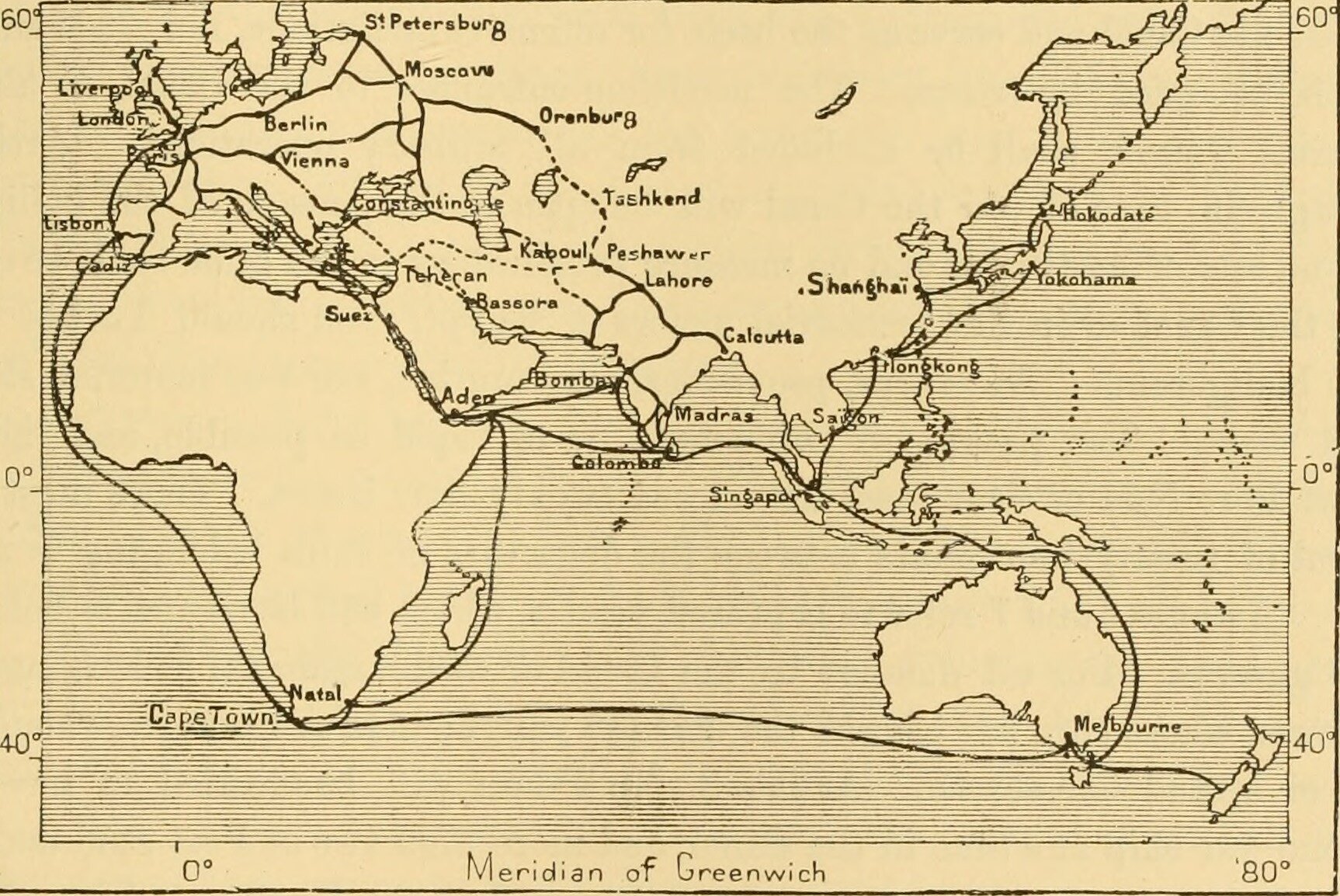

Image from page 454 of The Earth and its Inhabitants (1886). Sourced from the Internet Archive via Flickr.

Another useful map of the Suez canal can be found here.

Colonialism and competition between European nation-states had its origins in the monopoly companies in the early 17th century. There were constant violent struggles at every point in the colonial compass, all through these hundreds of years. The Spanish competed with the Dutch, English and French for the Americas; the English likewise competed with the same nations for India. Competitive colonialism was simply taken for granted as a fact of life in international relations. One of the underlying structural reasons that the European powers eventually went to war in 1914 was the unresolvable colonial conflicts between Germany and Britain and France. This will be dealt with in later blogs.

Over these 350 years, the major European powers were at war on their home soil or abroad against each other a great deal of the time. Wealth extraction throughout these years, as I have already argued, was a zero-sum game. The leading European powers developed sophisticated diplomatic skills, as we shall see in later blogs. A single nation could have more than a single goal at any one time, which would allow it to play as the cards fell. Alliances between nations became the name of the game, though they came and went according to circumstance and the assessment of advantage at any one moment.

As new colonising powers entered the race for wealth at the end of the 19th century, Italy moved into Eritrea, and Germany into south-west Africa and east Africa. Japan and the USA were intent on the Pacific and, in the US case, the West Indies. The demand for new territories was building, and tensions were rising. It is through understanding the centrality of competitive colonialism that we get to the heart of one of the fundamental causes of the 1914 war. ( I deal with the origins of the wars from 1914 to 1945 in future blogs in considerable detail) Britain, in particular, felt threatened at this time and wished to maintain her global ascendancy. The 1919 armistice at Versailles reflected these war aims. After 1945, the creation of the European Union created a sense of deep relief, which is reflected in the anger expressed when Britain decided to leave the Union in 2016.

Defending Colonies

A colonising power had to invade, conquer and rule territory. Then the new territory had to be defended: internally against uprisings by the conquered people, and externally against other potentially belligerent European powers. The coloniser preferred settlers from their people, both for defence against internal uprisings and externally against other aspirant colonisers. It was easier for London or Paris to deal directly with peoples from their own cultures and languages. That did not then mean a complete break, as had occurred in the USA in 1763. The British welcomed the developments in Australia, South Africa and New Zealand, and set up their own political administration in India. The French set up their own administration in Algeria. The colonial powers always maintained ultimate power and control from their capitals.

The smaller slave colonies in the West Indies were ruled with unmitigated violence. The white plantation owners were greatly outnumbered by the slaves, and the fear of slave revolts was continuous. When they were attempted in Haiti in 1795 and then in other West Indian islands, the violence of the repression was well beyond anything imaginable now.

European settlers invariably preferred self-rule. Defending territory, once conquered, caused multitudes of new problems: partially from internal rule but equally from external predators. Predatory action produced a complete break for the British and French when they lost the North Americas in the 1760s. In this case, it wasn't another European nation that caused the loss of territory; it was the settlers themselves who demanded and took self-rule by force of arms.

Britain quickly found that the Indian sub-continent was her favoured colony. It provided a constant flow of wealth to a multitude of individuals, a monopoly market for the British exports, and above all a large military machine which they did not have to pay for. But India was expensive to maintain. This was not from internal causes, rather most of the revenue collected from the peasants was spent on the Indian armed forces as they feared invasion from Russian expansion from the northeast. Whether these fears were realistic was never put to the test. But those fears were enough to lead the British into war with Afghanistan twice in the 19th century to protect their flank. The profits the British Indian government made from the opium trade were entirely swallowed up by their wars in Afghanistan.

The Suez Canal also caused a significant expense, as mentioned above. The canal was dug, in the middle of the 19th century, to provide a rapid system for moving shipping from Asia to Europe. The canal avoided the long voyage around the Cape in southern Africa, enabling ships to save additional weeks of travel time. This too needed defending against both the French and the local Mahdi.

The land-based empires of the period at least had an easier time compared to the predatory Europeans. The Russian and the US empires were both expanded by land, though under very different circumstances. Both were pushing their continental frontiers during the period under consideration. Throughout American expansionism across the continent, the Americans killed and removed the native peoples. Russia had been expanding from the 14th century; the Russian march across Asia incorporated the local peoples’ cultures into the Russian empire while providing space for Russian settlers.

Russia had driven across Siberia to the Far East and the Pacific from the 16th century. Importantly, people's economic and social structures were left largely as they had been found; the objective of the expansion had been the fur trade and trade with China. But after the defeat at the Crimean war of 1853-56, Russia turned her attentions to the east. This is not to suggest that that the Russian expansion was benign, it certainly wasn't. But it was not the holocaust that happened in the settling of the USA.

In this context, the Russian empire can be understood as a pre-capitalist colonial entity: they left the local peoples to their way of life, religion and methods of production. The US empire across North America was, by contrast, a capitalist empire, industrialised from the early 19th century. By killing and removing local peoples, there was no ancient culture to resist private property or new technologies.

Russian acquisitions and consolidation of her empire spread to Siberia, the Far East, the Caucasus and Central Asia, which included warm water ports. Russian expansion was then limited by British fears about expanding frontiers between India and Russia. Nobody ever came up with a solution to this question: how to defend your colony so that the rest of the world was also satisfied with the outcome. The world wars of the twentieth century certainly did not resolve these issues. Independence in the 1950s and 60s for old colonies began to prepare an answer. But the issues reappeared in a new form, as the USA attempted to reassert her control over the world’s newly sovereign states. Her answer was to create hundreds of military bases across the world.

Appendix

‘Competitive Colonialism’ is a concept of my creation as far as I can tell. I have not seen it being used elsewhere before.

‘Defending colonies’ is a process which is discussed in a variety of ways in many works.

See Robinson and Gallaher, Africa and the Victorians, I.B. Tauri (2015), for a detailed discussion about Egypt and the Suez Canal.

See Dalrymple, Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, Bloomsbury (2012) for information about the 19th Century Afghan wars.

Copyright Notice. This blog is published under Creative Commons licence. If anyone wishes to use any of the writing for scholarly or educational purposes they may do so long as they correctly attribute the author and the blog. If anyone wishes to use the material for commercial purpose of any kind, permission must be granted from the author.

The early Colonies from 1492 onwards were all ruled and settled by ‘white settlers.’ The areas settled included the Americas and to a small extent the Portuguese colonised Africa, and the Dutch settled in Southern Africa in 1652. All of these can be characterised as ‘settler colonies.’